For pilots, icing is an ugly word. It can be dangerous and unpredictable. The best defense in a perfect world is to avoid it altogether. Sometimes that isn’t an option and we get caught in it no matter how hard we try to avoid it.

For pilots, icing is an ugly word. It can be dangerous and unpredictable. The best defense in a perfect world is to avoid it altogether. Sometimes that isn’t an option and we get caught in it no matter how hard we try to avoid it.

Flying in weather is all about managing risk. There are a number of systems used to manage risk when flying in icing conditions and they fall into two categories: deicing systems (which will be the focus of this article) and anti-icing systems. Surprisingly the two terms get used interchangeably but the truth is deicing systems are designed to remove ice that has already accumulated on critical surfaces and anti-icing systems are designed to prevent ice from accumulating on those surfaces in the first place. There are different methods and systems currently in use. All have their advantages and disadvantages and there is no one perfect system. This article will focus on the pneumatic deice system – “boots” – that is the most common on factory production aircraft and repeatedly has stood the test of time.

It may surprise you to know that deicers have been around since 1929 when first invented by Dr. William Geer. Though the concept has not changed much since then, technology has made major strides and materials are much improved.

Pneumatic deicers are primarily designed to be attached to the leading edges of the wings and tail. Some aircraft even have them attached to the wing struts and cargo pods on the belly. The purpose is to help shed ice accumulation by inflating air channels incased in neoprene and rubber layers and then deflating to re-conform to the airfoil shape. This can either be done manually or automatically by a cyclic timer.

Pneumatic deicers are primarily designed to be attached to the leading edges of the wings and tail. Some aircraft even have them attached to the wing struts and cargo pods on the belly. The purpose is to help shed ice accumulation by inflating air channels incased in neoprene and rubber layers and then deflating to re-conform to the airfoil shape. This can either be done manually or automatically by a cyclic timer.

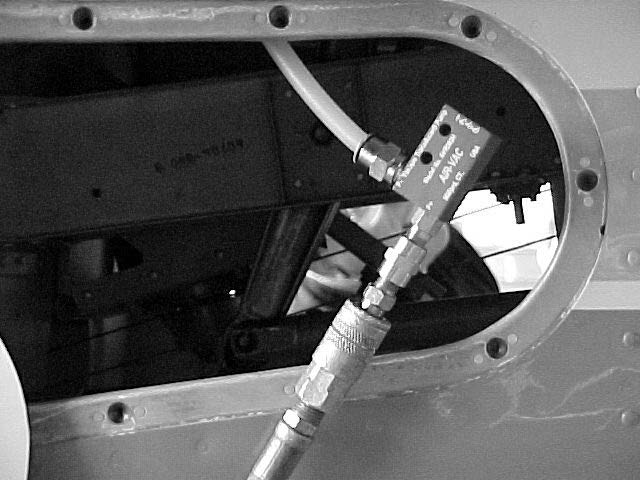

Although systems will vary somewhat from one aircraft make to another, the basic components of any system are similar. Most will consist of a pneumatic system (air pump, regulator, vacuum gauge, tubing and filters), deice boots, timer, on/off switches, and relay(s) for inflation sequencing. The air pump provides a pressure source and a vacuum source.

It is the heart of the system. In turbine aircraft the air source is bleed air tapped from the engine. These components are sometimes overlooked by the owner/operator during inspection but they should be given regular maintenance. As a manufacturer of deicers we often get questions from owner/operators and pilots about the “care and feeding” of deicers. Most want to know what products to use to make them shiny. While important, first it is important to understand the system since cosmetics and performance differ greatly.

It is not uncommon to see a pilot during a preflight dutifully running his hand over the leading edge of the wing looking for something out of order. What is discovered most often are either small tears in the outer layer of the boot or small pinholes. Often these can be repaired with a patch or a pinhole repair kit. If the tear is too large for a patch, or if the tear or cut reaches the inner fabric and damages it, the boot must be replaced. There are limits to the sizes and number of patches a boot can have as well as the size and number of pinhole repairs for a given area.

It is important to note that patches have an orientation to them and must be installed accordingly. Just like the deice boot, patches are designed to stretch in one direction – usually horizontally. Patches must also extend 1/2” minimum beyond the damaged area. Pinholes that are larger than 1/16” must be repaired with a patch and not with a pinhole repair kit. The maximum amount of cumulative patch or pinhole repair area per boot is a 12 inch square area. Notice I did not say 12 square inch area. Imagine if you will a picture frame that is 12 inches on each side with no picture in it. The patches or pinhole repairs are relegated to the area that frame would cover if laid over the boot. Some examples of allowable quantities for patches within the 12 inch square area are: 3 small patches, 2 medium and 1 small patch, or no more than 20 pinholes.

It is important to note that patches have an orientation to them and must be installed accordingly. Just like the deice boot, patches are designed to stretch in one direction – usually horizontally. Patches must also extend 1/2” minimum beyond the damaged area. Pinholes that are larger than 1/16” must be repaired with a patch and not with a pinhole repair kit. The maximum amount of cumulative patch or pinhole repair area per boot is a 12 inch square area. Notice I did not say 12 square inch area. Imagine if you will a picture frame that is 12 inches on each side with no picture in it. The patches or pinhole repairs are relegated to the area that frame would cover if laid over the boot. Some examples of allowable quantities for patches within the 12 inch square area are: 3 small patches, 2 medium and 1 small patch, or no more than 20 pinholes.

More information on patch size and correct installation of patches can be found at www.iceshield.com/documentationManuals.asp.

More on pinholes and boot maintenance in Part 2 of this article next week!

By: Steve Mayer, GlobalParts.aero

www.globalparts.aero